Week 3: Spheres of exchange, in comparative and historical perspective

When the norm of reciprocity meets the logic of capital

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology for a better world

ryan.schram@sydney.edu.au

Social Sciences Building 410

August 19, 2025

Lecture outline available at: https://anthrograph.rschram.org/1002/2025/03

Main reading: Swanson (2014a)

Other reading: Swanson (2014b); Deomampo (2019)

Did you register for the class last week?

Welcome to the class. If you have just joined ANTH 1002:

Log on to Canvas today, read the preliminary materials for the class, and my recent announcements to the class.

Read the instructions for the assignments, including the general instructions for weekly writing assignments and the information about the Week 3 “early feedback” out-of-class quiz.

Say hello to your fellow students on the Discussions page.

Two new tutorials at 5 p.m. on Friday are being added now. See my announcement on Canvas about how to add yourself to the new tuts or ask to add to another tut with space. (Not everyone will get their first choice of tut and Ryan is not moving students to accommodate their preferences.)

Is everything a gift? Really?

Mauss argues that every exchange is a gift, and every gift comes with three obligations: to give, to receive, and to reciprocate

You may be skeptical. That’s good. Stay skeptical.

In the contemporary world, every one of us, and most people on Earth, will meet some needs by buying and selling. Typically buying and selling does not involve ongoing ties of interdependence.

Then again, we should not assume that self-interested economic transactions are universal either, and that every exchange is also an example of rational maximization by individuals.

Karl Marx’s theory of capitalism gives us a new perspective on markets

Like Mauss, Marx also challenges the idea that economic self-interest and rational maximization are part of a universal human nature.

Mauss tells us to think globally. Marx tells us to look at history.

People have used money and currency of some kind for 1000s of years. That’s not new.

What is new is the idea that owning also gives the owner a right to deny its use to other people. Private property is exclusive ownership. This is a new invention.

When a society protects private property, then rich people can own all of the productive resources (capital) that a society needs to meet everyone’s needs. One class owns all the capital; everyone else has no say over a society’s means of production.

The new ruling class—the owners of capital, or the bourgeoisie—produce commodities with other people’s labor.

The logic of capitalism is antithetical to a system of total services

Under a capitalist system, the main form that value takes is as a commodity.

- Valuable, useful things are packaged so they can bought and sold for a profit.

With the rise of capitalism, people are also influenced by the culture of the bourgeoisie, based on individual choice, freedom, and the right to own capital as private property.

- When you meet your own needs by consuming commodities, you also pretend you are an individual who is making rational choices.

Even if you are opposed to private property and commodification of value, it’s easy to assume that these changes are inevitable.

Not so fast. In practice, capitalism is neither a utopia nor a dystopia.

What is Mauss really saying?

When you first hear Mauss’s ideas, it may sound like there are two types of society:

- Societies based on gifts and reciprocity

- Societies based on private property, capitalism, and markets

This is how Mauss sounds if you look at the world through the lenses that bourgeois culture gives you.

No. Mauss is arguing for a new view of all societies.

The pull of reciprocity, and of the social whole, is still there even as commodification challenges it.

Is everything for sale?

What did you write about for this week?

Share with each other.

- If something cannot be sold, what can you do with it?

An editorial decision

Portland, Oregon, 1997. The Reed College Quest editors meet to discuss an inquiry about a classified ad.

Nobody involved can remember what it said. It was something like this:

“WANTED Healthy female student to help bring joy to an infertile couple. Will pay $3000 plus all medical expenses for a donation of several eggs. Candidates should have a minimum GPA of 3.5 and minimum combined SAT scores of 1600.”

(GPA: grade point average, 3.5 is approximately a WAM of 80. SATs are college entrace exams. Under the old system, 1600 would have been close to an ATAR of 95.)

Meanwhile…

Wendie Wilson was a student at the University of Washington around the same time. She volunteered to give several eggs for $5000.

“It seemed a relatively small amount of my time for what seemed to be pretty decent compensation.” It was empowering (Tuller 2010).

She later founded an egg donor registry, Gifted Journeys.

Human trafficking?

A friend recalls similar ads in student publications at a university in Vancouver, British Columbia. “We had ads at my college in Canada too, even though selling eggs isn’t legal there. I guess they would ship you to the US for the procedure” (personal communication, 2014).

What the ads ask for

- University students (women who have more and better-quality ova).

- Preferred hair and eye color.

- Preferred race.

- Preferred school. Ivy-league (Harvard, Yale, etc.) schools are especially popular, as are Berkeley and Stanford.

Not for sale?

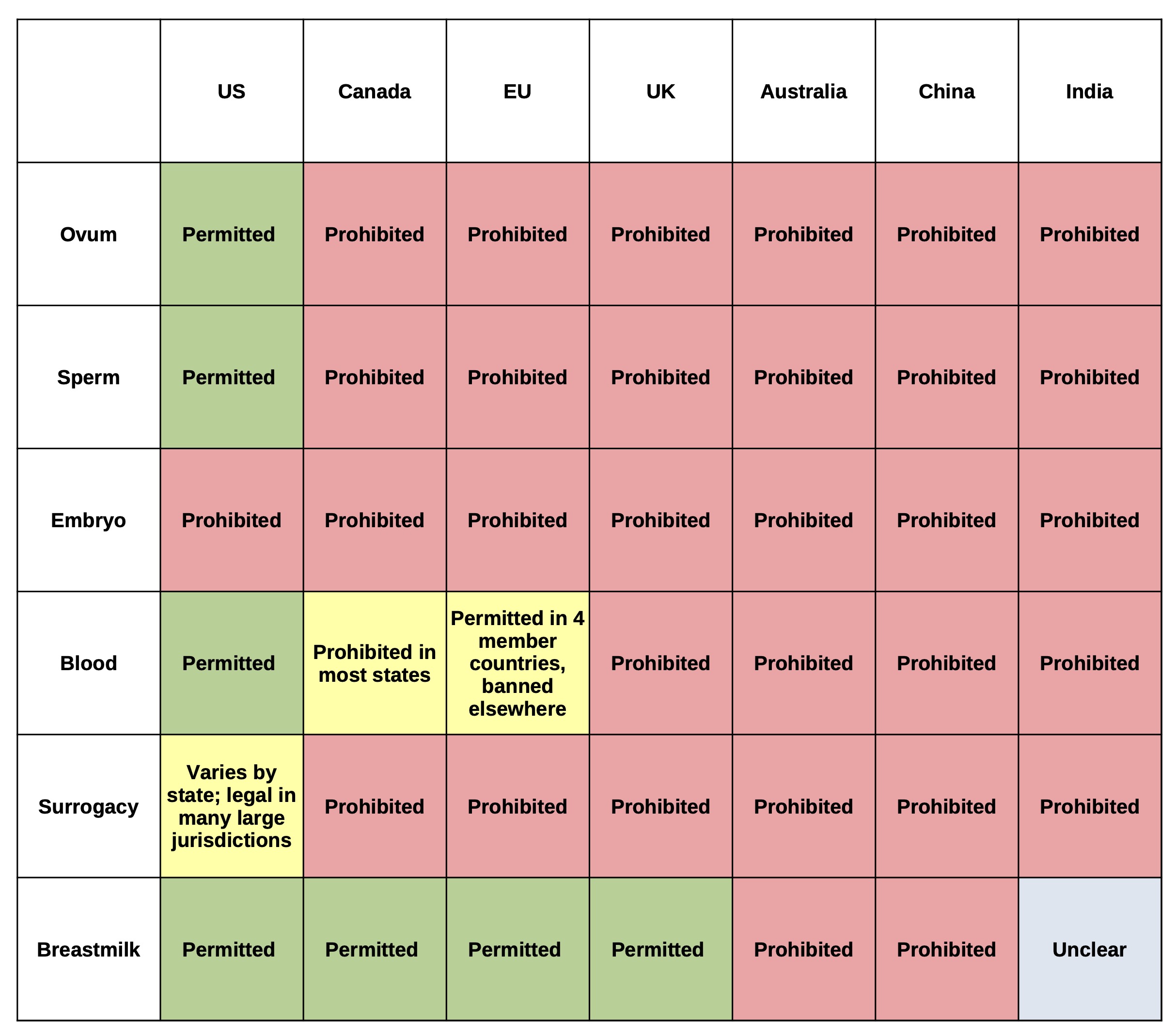

Unlike many countries, the sale of gametes is largely unregulated in the US, and the US has generally looser regulations on IVF and surrogacy. (PDF version.)

Why do some people exchange breastmilk? Why do some societies prohibit its exchange?

There are many different ways that people circulate breastmilk, both in exchange for money and without exchanging money.

- In many societies, mothers offer the service of breastfeeding to

each others’ children.

- This even creates “milk kinship” among children fed by the same woman. Nursing makes a baby your child, and two children of the same nurse are siblings (Clarke 2007).

- For that reason, Islamic teachings forbid milk banking. Donated milk can’t be anonymous. What if the recipients get married? (Ghaly 2012)

- There are groups in Australia who want to promote voluntary, unpaid

wet nursing (Zillman 2019).

- The Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA) calls milk sharing “cross-feeding” and considers it and other kinds of sharing risky (“Donor Milk” 2022).

- They promote “milk banking” which accepts donations of milk which are sterilized. Donating is OK only if it is anonymous and entails no social embeddedness or ongoing obligations.

- In 2017, the Cambodian government banned the sale of breastmilk in response to the arrival of a US corporation which produces milk products (Wong 2017).

The influence of Marcel Mauss is wide, even if people depart from his words

Spheres of exchange are moral boundaries in a double sense:

- The difference between two spheres is a collective representation, a social construct thought by the collective mind of society.

- As a social construct, it is also intimately tied to and reinforces the society’s existence as a system of total services, a state of total interdependence among all people in one group.

Mauss’s ideas cast a long shadow across many fields

The question of whether and why there are limits of capitalist commodification is something all social scientists want to understand, and legal scholars like Kara Swanson as well.

- Swanson is influenced by sociologists who want to know why moral ideas influence social institutions, and these sociologists draw on Durkheim and Mauss’s ideas.

- Like Mauss and Durkheim, Swanson wants us to see the invisible boundaries constructed by the collective consciousness of society because this, she would say, is where a society’s laws come from.

- She wants to challenge the bourgeois ideological fiction now

reflected in law that things are either

altruistic gifts or commodities. In this respect, she

agrees with Mauss. Everything shares in the logic of reciprocity.

- Her point, in my reading, is that US culture strips the obligations from the gift.

- A better phrase for Swanson would be the altruism–self-interest dichotomy.

Every society is a product of history, and the incorporation of commodity exchange is a big part of every contemporary society’s story

In a bourgeois way of thinking, one can either give something freely with no obligations of reciprocity or one can buy and sell things.

- For this reason, US social and medical institutions are very anxious about exchanging breastmilk. They can’t tell what it means, so they create rules that prevent commercialization.

The same ideology can lead people to see alternative economies in ethnocentric terms

- In a bourgeois perspective, Tiv society lacks something that modern societies have: They have spheres of exchange because they have not learned how to act like rational individuals in a market.

Reciprocity and commodification exist in every society, but they resist each other

- No society exists in isolation. Every society has a history.

- For that reason a society is not one single essence, and cannot be classified as either one kind or another kind of society.

- The encounter between reciprocity and capitalist commodification is

a major part of every society’s contemporary history.

- When they come together, they push against each other, like two opposed magnets.

Tiv spheres in a colonial context

According to Guyer (2004), the Tiv spheres of exchange are not a tradition, and not frozen in time. They are a historical phenomenon.

- Brass rods work like a kind of currency (noted also by Bohannan), but this a medium of exchange that Tiv keep out of the hands of banks.

- Cash transactions are morally judged, but not because spending money is prohibited or sinful. Money-exchange means a loss of control over Tiv people’s collective wealth as a community.

- Suspicion of money is a political statement, not by an individual ideologue, a political party, or an organization—but by the social whole itself.

Taro gardening in Wamira, PNG and Luo land ownership in Kenya

One of the ways societies respond to market forces is by placing limits on individual choices

- Wamira (Papua New Guinea) taro gardens can’t be tended with metal tools (Kahn 1986)

- When Luo (Kenya) people sell land, they earn “bitter money” (Shipton 1989)

Potlatch: Giving and global trade

In the 18th and 19th centuries, and after a revival in the 20th century, Indigenous societies of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America celebrated huge feasts known as potlatch (which means to give)

- Gifts exchanged between different communities’ leaders were competitive in nature, each trying to give more than the other could give back (Mauss [1925] 1990, 6–7, 38–40; Eriksen 2015, 224–25).

European presence in North America after 1800 gave people more sources of wealth for potlatch gifts, and potlatch prestations grew (Wolf 1982, 184–92).

- Colonial contact did not compel people to abandon potlatching, but stimulated its growth and expansion, until it was banned by Canadian law as a political threat (which was repealed in 1951).

The efflorescence of exchange

“The first commercial impulse of the local people is not to become just like [the West], but more like themselves” (Sahlins 1992, 13).

As a Kewa leader once told an anthropologist (paraphrase): “You know what we mean by ‘development?’: building a hauslain [a village community], a men’s house, and killing pigs. This we have done (quoted in Sahlins 1992, 14).

Change in a society may look like what bourgeois culture says is development, but it could be that you mistake what you are seeing

- In rural PNG societies to develop is really the enrichment of their own ideas of what mankind is all about (Sahlins 1992, 14).

Ongka’s “big moka” is an example of efflorescence in PNG. Is there an example of develop-man in Sydney or where you live?

Recap: What happens when reciprocity and commodification meet?

A society may attempt to strip away the obligations of the gift (or impose an altruism–self-interest dichotomy on all exchanges).

It might segregate reciprocal exchange and market trade to different spheres.

It might subordinate commercial profit to the sphere of competitive reciprocity, leading to an efflorescence of a society’s total system of reciprocal ties.

AI acknowledgement

Portions of the reading script were generated by Google Gemini, an LLM, from an audio transcript based on the following prompt: “This is an audio transcript. Please correct it to use full sentences in connected prose, correcting errors of grammar, spelling, and punctuation, but preserving all of the original text. Correct spellings of these names and phrases: Emile Durkheim, Marcel Mauss, Auhelawa, Karl Marx,”gift/commodity dichotomy” and “altruism/self-interest dichotomy.” Add an acknowledgement of AI use at the end including the text of this prompt.” The text was then extensively corrected and edited by the original author.